iQube

An interactive puzzle platform for children that helps foster mental agility and problem solving skills.

The Project

For the fifth design studio in the sequence for my product design degree, we visited a local middle school where we were tasked with designing a piece of technology to enhance the students’ educational experience.

Over the course of the semester we met with teachers and students to identify problems and test prototypes. I worked with another student, Dominic Gelfuso, on this project.

The People

preliminary Interviews

On our first day we met with the teacher of the class we’d be working with as well as the principal of the school. They told us that many of the students were engaged enough at school but that many lacked a constructive environment at home. They believed this to be responsible for a drop off of engagement as kids got older and further along in the school system.

They also showed us an online learning environment that they had recently employed for enrichment in reading and math that had apparently boosted test scores considerably. It seemed, unsurprisingly to us, that the kids were really drawn to technology even if it was for educational purposes.

We knew that many of the kids were from economically struggling families. One interesting thing we learned was that though nearly none of the kids had access to a computer at home, almost all of them owned one or more video game consoles. The school’s principal told us that many parents would find a way to get a game console for their kids to give them a more normal and fun childhood, even if it was something they couldn’t easily afford. For this reason games had a special significance for these kids.

Meeting the kids

Our first meeting with the students was brief but informative. We spoke to them in groups of 4-5 and rotated every 5 minutes. We asked them general questions about their interests and hobbies, what they liked about school and where they struggled, what they did in their free time, what they thought they wanted to do when they grew up. We knew each group would get asked the same questions a number of times so we tried to keep it casual and conversational.

We found that these were, indeed, normal 10-11 year old kids. They played a lot of video games and sports. Many loved to read and draw. We were surprised to find that the majority of kids said math was their favorite subject but later found out that we had interviewed them while they were in homeroom with their math teacher.

The most interesting responses we got were to the question, “what part of the day do you most look forward to and what part don’t you?”. Some looked forward to specific classes like science or social studies, some to lunch and recess, others to the end of the day. But many of the students said they really dreaded classes where the teacher would call on them if they didn’t raise their hand and classes were they had to speak in front of the class.

Coming from a design program where we’re always sharing ideas and often presenting to large groups, we could relate to their anxiety but knew that they’d be leagues ahed the sooner they could overcome it and not be afraid to express themselves; to not be afraid to be wrong or to fail. This gave us some direction.

Prototype 1 - Double Trouble Puzzle

In the context of play the students were much less reserved about trying problems that they weren’t sure they could solve than when in the classroom proper.

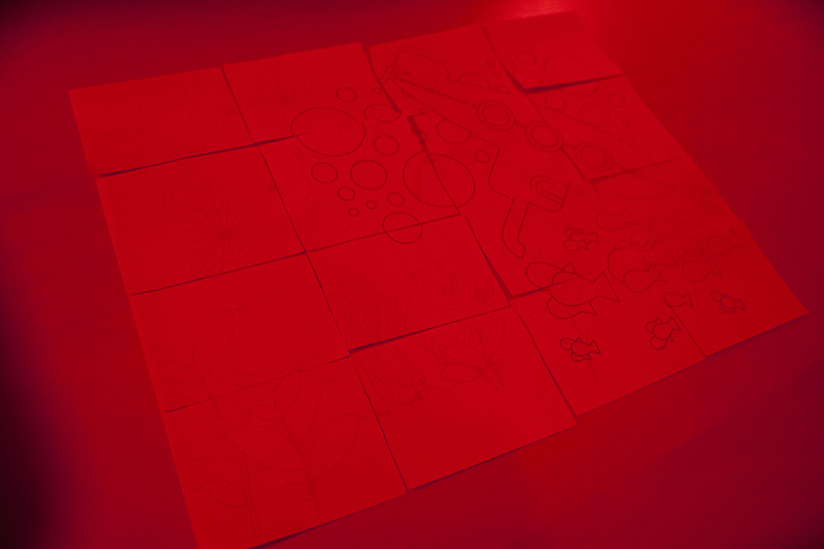

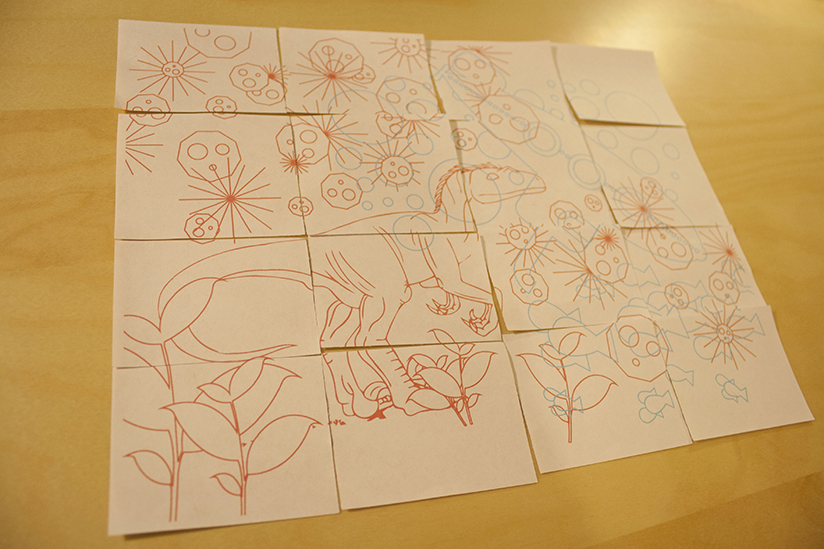

We developed puzzle with two unrelated images that overlapped — one printed in red and the other in cyan. We asked two students, one with red tinted glasses and another with cyan tinted glasses to work together to put the pieces together.

Informed by our first interview with the students, we wanted to create something that got them interacting with one another and challenged them to work together and communicate.

We developed a puzzle that had two unrelated images that overlapped — one printed in red and the other in cyan. We took two students and gave one red tinted glasses and the other cyan tinted glasses, so that each student could only see one of the images, and then had them work together to put the pieces together. We specifically overlapped the images so that parts would be difficult to solve by just one person.

Looking through the cyan lens one can only see the image of the dinosaur printed in red.

Looking through the red lens one can only see the image of the submarine printed in cyan.

Both participants need to work together to solve the middle of the puzzle where the images overlap.

We were glad to see that this exercise inspired a lot of talking and team work (and that the kids were actually entertained). In some cases one student took more of a lead but even then there were points were they came together. This exercise taught us a lot about the way the students engage with problems and with their peers to solve them. It seemed that in the context of play the students were much less reserved about trying problems that they weren’t sure they could solve than when in the classroom proper.

Finding Direction

It was an arbitrary requirement of our class to use the Arduino in our project, so we began thinking about how to apply our experience from our first prototype into a more interactive piece of technology.

Because we knew the kids had an affinity for technology and games, and because we saw the effectiveness of taking problem solving out of it’s traditional context and into the domain of play, we decided to make some kind of interactive puzzle. We wanted to make something engaging and fun that encouraged problem solving and thinking outside the box. However we also had to deal with the constraints of having a working prototype built in under three weeks and the fact that neither of us had experience working with Arduino before.

We ultimately decided on a cube shaped puzzle, with a screen on each face, where students would interact with information across all six faces. We weren’t quite sure about what the puzzle would be but were compelled by the idea of working with information across space, where you couldn’t see all the information at once. We also imagined that the cube could be a platform for multiple games.

We chose a cube because it was vaguely mathematical, was familiar and simple but could be made into an engaging and pleasant object and definitely because me and my teammate had fond memories of playing with Rubiks cubes (I know, we’re nerds).

Prototype 2 – Playing Outside The Box… And Around It

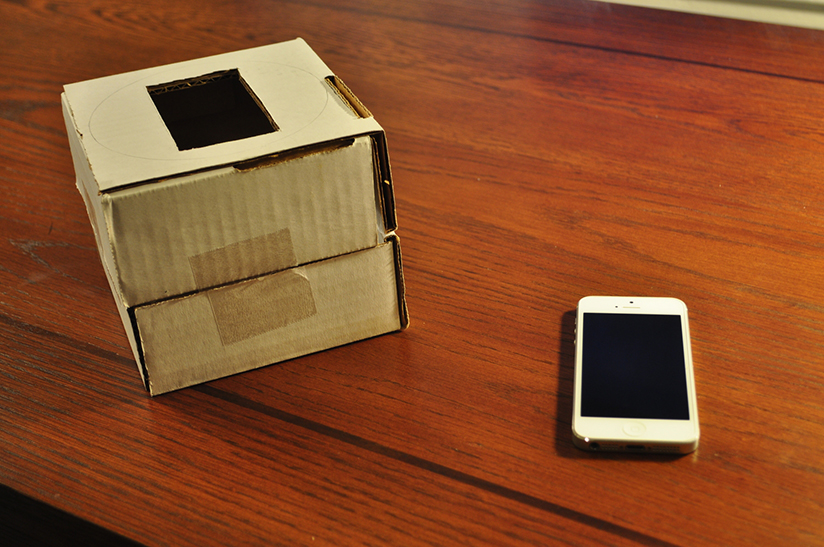

We developed a prototype which utilized a small web-app that I built which was displayed on an iPhone in a cardboard box. Making use of the phone’s accelerometer students would tilt the box to reveal answers to a trivia question on the center of the screen.

We developed a prototype which utilized a small web-app that I built, which was displayed on an iPhone in a cardboard box. Making use of the phone’s accelerometer students would tilt the box to reveal answers to a trivia question on the center of the screen. Though this only had students engaging with one side of the cube this helped us determine how engaging the cube format was for the students.

They seemed pretty compelled by the prototype even though the trivia questions were, well, trivial. Although I think they were also excited to play with an iPhone in a box (who wouldn’t be) and many asked if I had their favorite apps installed.

They seemed to have an intuitive understanding of tilt based controls and did seem to be engaged by controlling the screen by moving the cube so we decided to move forward with the cube idea.

Screenshots from the trivia game we created. a question was displayed on one face and tilting the phone revealed possible answers on the other virtual faces. An answer is selected by tilting the cube such that the answer fills the whole screen. The screen flashes to show if an answer is correct.

Final Prototype - IQube

Our final prototype consisted of a 3D printed shell with 6 8x8 LED matrices of varying color and an accelerometer/gyroscope chip. Each screen displayed a shape and rotating the cube rotated the shape facing up relative to the user. The object of the puzzle was to rotate the shapes so that they connected, forming a continuous line across the cube.

Our final prototype consisted of a 3D printed shell with 6 8x8 LED matrices of varying color and an accelerometer/gyroscope chip. Each screen displayed a shape and rotating the cube rotated the shape facing up relative to the user.

My partner built the prototype and I programed the Arduino chip that powered it. I had no experience with Arduino before this project but was able to hack together code that worked decently well. We were able to have the students test our device and gained valuable feedback.

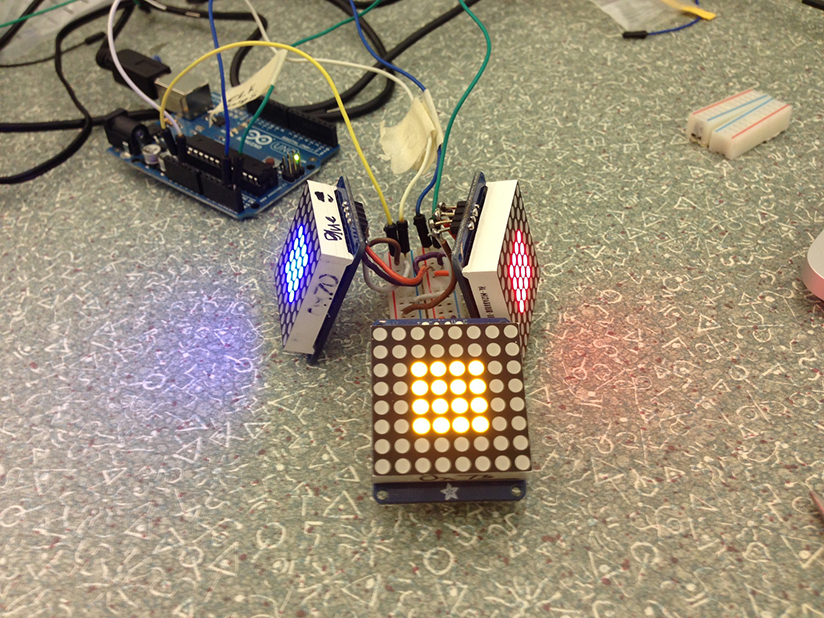

The guts of the iQube — testing three of our screens

It was a simple puzzle — the best we could do with our limited time, money and experience — but the kids seemed to really enjoy it. We didn’t explain the puzzle to them and many figured out intuitively what they had to do. Many teamed up, having one student watch the faces that were on the underside of the cube and give directions to the student solving it. They were all relatively engaged for the first use but after solving it once, or watching others solve it they got bored, which was to be expected. If we had more time we would have liked to create more puzzles and use higher resolution screens.

This was one of the most valuable design experiences I’ve had so far because of how closely we got to work with the actual users of our product. It would have been nice to have more time and not have the arbitrary constraint of using the arduino, but I think overall our product was successful and I learned a lot from the process.